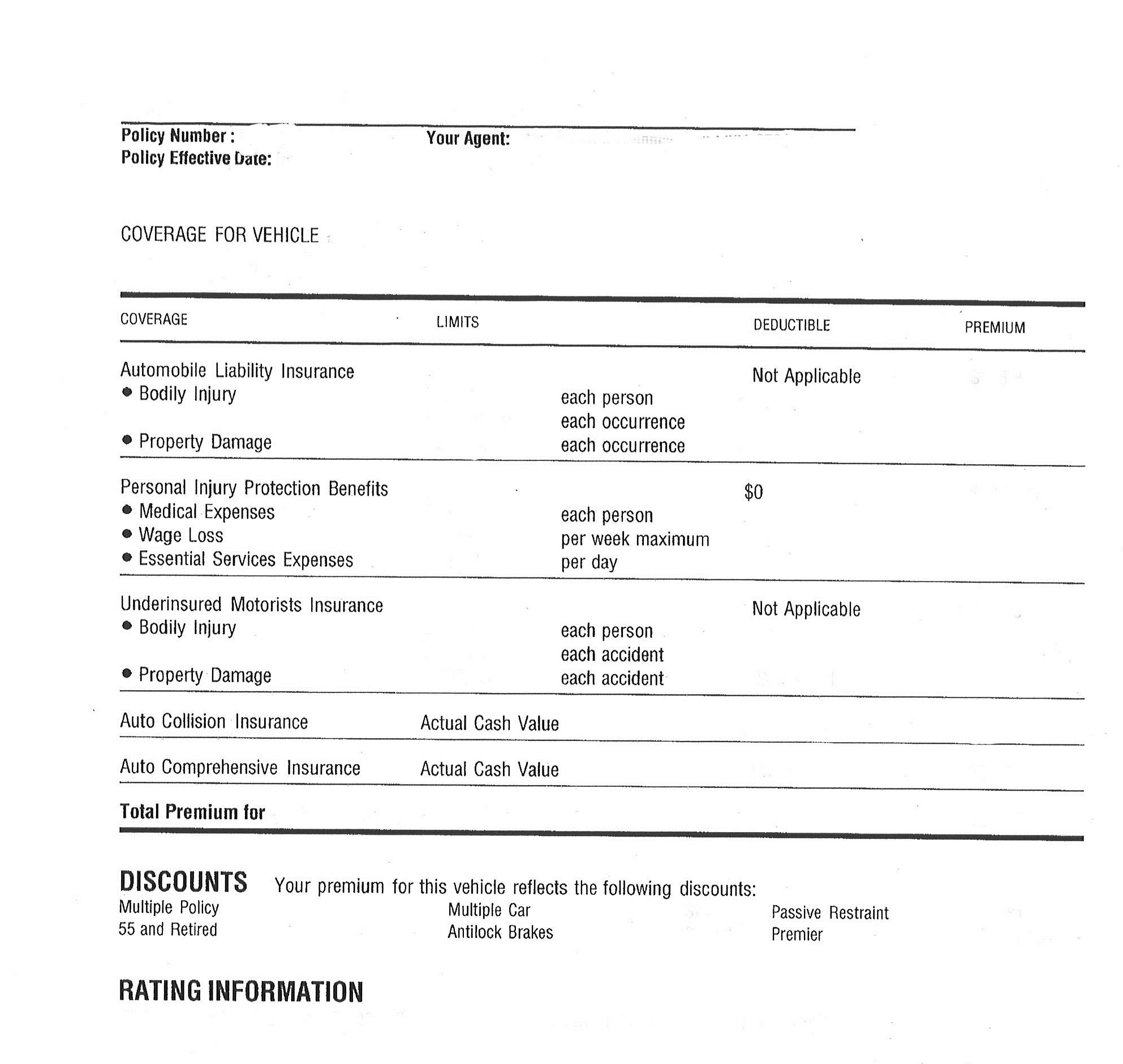

We may collect personal information from you such as identifying information (name, address, driver's license number), transactional information , digital network activity , geo-location data, audio recordings and other forms of personal information. In 1962, State Farm offered auto insurance for 20% savings to students who were doing well in school, based on the hope that if they were home studying for their good grades, they would be less likely to be out driving cars. In 1963 the company instituted monthly premium payments, and agents were authorized to make on-the-spot auto claim payments of up to $250, which improved customer service considerably.

In 1965 State Farm began offering limited health insurance. The policy offered $15 for every day a policyholder spent in the hospital. This payment was touted as a possible supplement to other health insurance a person may have, perhaps to help pay for a babysitter or a housekeeper while a mother was away from home. In 1962, State Farm offered auto insurance at a 20 percent savings to students who were doing well in school, based on the hope that if they were home studying for their good grades, they would be less likely to be out driving cars. In 1963, the company instituted monthly premium payments, and agents were authorized to make on-the-spot auto claim payments of up to $250, which improved customer service considerably. In 1965, State Farm began offering limited health insurance.

State Farm is a mutual company as opposed to either a private or public company. In the case of a private firm, the customers have no stake whatsoever in the company's success or failure, whereas a public firm's stockholders gain or lose depending on the company's performance. A mutual insurance company will raise the cost of premiums across the board depending on the balance of claims versus payments in a given year. For instance, if there are a particularly high number of auto accidents and natural disasters one year, more people will collect on their policies, and if this exceeds the money taken in by the company, everyone's rates may rise.

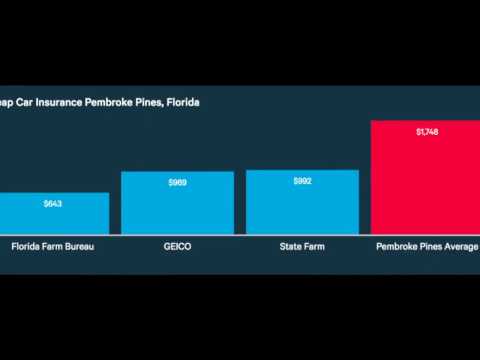

If there are fewer claims than expected, the mutual insurance company may present its customers with dividend checks. Auto insurers had to contend with one of the broadest target audiences in all of marketing. The law required every driver to be insured, creating a massive pool of potential clients that encompassed all genders, races, and ages. The younger demographic, however, was more price-conscious and had not grown up with the assumption that one did business with an agent. In fact, many of them preferred not to have a relationship with an agent and were more than willing to switch insurance companies if the price was right.

The campaign also sought to persuade other older drivers of the importance of what State Farm had to offer. At the same time the company was not writing off younger customers. One of the television commercials focused on a young woman who had two accidents within her first hour of having a driver's license. State Farm was founded in June 1922 by retired farmer George J. Mecherle as a mutual automobile insurance company owned by its policyholders.

The firm specialized in auto insurance for farmers and later expanded services into other types of insurance, such as homeowners and life insurance, and then to banking and financial services. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Company, the cornerstone in the State Farm Insurance Companies group, has been the number one automobile insurer in the United States since 1942. Approximately one out of five cars in the United States is insured through State Farm. Through a network of over 16,700 agents, the company and its subsidiaries handle 71 million auto, home, life, and health insurance policies.

The State Farm group also offers its customers mutual funds and a variety of banking services, including deposit accounts, CDs, and mortgages via the Internet and telephone. Nonetheless, Plaintiffs argue that the trial court erred as a legal matter for two reasons, both of which we find unpersuasive. First, Plaintiffs claim that the trial court failed to understand its two class-wide theories of proof. Plaintiffs claim that they can prove liability by simply showing that State Farm's process for reviewing claims was inadequate or that it relied solely on a flawed database to reprice claims.

Then, if State Farm breached its contractual or statutory obligations, Plaintiffs claim that it would be liable for the amount established by properly submitted medical claims. See § 10–4–708, C.R.S. ("Benefits for any period are overdue if not paid within thirty days after the insurer receives reasonable proof of the fact and amount of expenses incurred during that period[.]"). Plaintiffs thus argue that there is no need to conduct individual inquiries into the reasonableness of each medical bill. Accordingly, they urge us to conclude that the trial court erred as a matter of law when it denied class certification on the grounds that the central issue of liability is the reasonableness of each medical claim.

Plaintiffs also argue that State Farm is effectively barred from relying on evidence other than the database. Plaintiffs claim that State Farm cited only the database as the basis for denying claims, and thus is limited to that explanation at trial. As a result, Plaintiffs claim that determining liability pivots solely on evidence regarding the database which, by definition, is common to the class. However, "n insurer's decision to deny benefits to its insured must be evaluated based on the information before the insurer at the time of that decision." Peiffer v. State Farm Mut.

Here, as the trial court found, State Farm did not rely solely on the database to review every claim, but rather had a three-step claim review process. It is therefore entitled to present all the information it used in reviewing each claim. Accordingly, because the trial court conducted a rigorous analysis of the evidence in making its class certification decision, we discern no abuse of discretion in its C.R.C.P. 23 determination. State Farm raises two challenges to the court of appeals' determination that common issues predominate over individual issues for the purposes of C.R.C.P. 23.

First, State Farm argues that the court of appeals erred in evaluating predominance based on Plaintiffs' mere allegations of a class-wide theory of proof, rather than on the evidence submitted with regard to class certification. Alternatively, State Farm argues that the need to individually analyze whether each class member was injured precludes a determination that common issues predominate over individual issues. The Progressive Corporation also beefed up its marketing budget to make its own price pitch. In 2004 State Farm released a new advertising campaign created by ad agency DDB Chicago. Called "True Stories," it made the case that an agent-client relationship was important.

Applying that standard here, we find that the trial court rigorously analyzed Plaintiffs' proposed class-wide theories of liability as well as the evidence offered by State Farm to refute those theories. Plaintiffs argue that State Farm did not produce any evidence to rebut Plaintiffs' showing that State Farm relied solely on the database. During the 1980s, the property and casualty insurance industry was rocked by a number of problems. The industry suffered sharp increases in claims costs, especially naturaldisaster claims and environmental-cleanup costs in the commercial arena.

The rising costs of car parts, labor, medical treatment, and litigation is also impacting the cost of insurance, and customers are complaining. The industry suffered sharp increases in claims costs, especially natural-disaster claims and environmental-cleanup costs in the commercial arena. The rising cost of car parts, labor, medical treatment, and litigation was also impacting the cost of insurance, and customers were complaining. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Company operates as an insurance company. The Company offers vehicle, auto, accident, homeowners, condo owners, renters, life and annuities, fire and casualty, health, disability, flood, business, and boat insurance products and services.

State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance serves clients in the United States. In other words, the trial court determined, by a preponderance of the evidence, see Jackson v. Unocal, 262 P.3d 874 (Colo.2011) (Eid, J., dissenting), that individualized issues would predominate over common issues, thus precluding class certification. Because I find that the trial court did not abuse its discretion in denying certification in this case, I concur in the result reached by the majority. In this case, the court of appeals applied the incorrect standard to determine whether Plaintiffs had established the class certification requirements. The court of appeals did not dispute the trial court's analysis of the evidence presented, but rather believed it was bound to accept Plaintiffs' allegations as true. The court of appeals explained that any factual dispute regarding State Farm's reliance on the database was "an attack on the merits" that could not be resolved at the class certification stage.

Reyher II, 230 P.3d at 1258 (quoting Burgess v. Farmers Ins. Co., 151 P.3d 92, 99–100 (Okla.2006)). The court of appeals thus accepted at face value Plaintiffs' allegations that State Farm had a practice of relying solely on the database to assess the reasonableness of claims and reprice them accordingly. As a result, the court of appeals concluded that Plaintiffs could "conceivably prove" State Farm's liability on a class-wide basis.

After considering this testimony, the trial court identified numerous questions regarding the reasonableness of the medical claims which, the court determined, could not be answered by evidence common to the class. Although the trial court recognized several issues common to the class, the court concluded that individual issues predominate and refused to certify the class. In light of the trial court's rigorous analysis of the evidence, we cannot say that this decision was an abuse of discretion.

The issue most relevant to the predominance requirement, and thus to the maintenance of the class in this case, is whether the Plaintiffs have advanced a class-wide method of proving that State Farm violated the No–Fault Act and its contracts with insureds. Plaintiffs claim that they have two class-wide theories of proving liability that obviate the need for individual inquiries into the reasonableness of each medical bill. First, Plaintiffs allege that they can establish liability with common evidence based on State Farm's failure to implement reasonable standards for investigation as required by the No–Fault Act and its contracts.

The trial court denied the motion for class certification on the grounds that Plaintiffs had failed, among other things, to establish C.R.C.P. 23's predominance requirement. The court explained that the central question in the case—determining the reasonableness of medical bills submitted to State Farm—would require analyzing the facts of each claim. As a result, the court determined that the individual issues of each claim would predominate over issues common to the class. The 30-second television spots were first shown during baseball's World Series, which was telecast on the Fox network on October 23, 2004. Subsequently the commercials aired on major network shows and cable programming.

In addition to the general-market spots, the campaign included the creation of single spots aimed at the African-American, Hispanic, and Chinese-American markets . The spot called "Diver" featured Wisconsin State Farm agent Larry Bitterman, who served an out-of-town State Farm driver whose car had somehow fallen into a lake as a result of a faulty map. Not only did Bitterman settle the claim, but he also helped raise the car from the lake in his capacity as local diver.

The "New Driver" spot showed a State Farm agent providing counsel for a San Jose, California, teenager who crashed her car twice in 10 seconds, within 45 minutes of receiving her driver's license. Her tale was interwoven with commentary from her parents and brothers. Other spots included Roisum's newlyweds as well as twin sisters who had accidents in the same intersection. The six agent stories were also fleshed out on the Internet as interactive ads. Radio versions of the television spots were created, and the campaign included a handful of print ads, but television was far and away the main messenger.

Although one spot touted State Farm's financial services, the campaign focused on car insurance. State Farm also argues that individual issues predominate over common issues because Plaintiffs cannot prove liability without demonstrating that each insured and provider suffered injury. This conclusion conforms with our recent decision in Garcia v. Medved, Inc. There, class certification turned on the plaintiffs' ability to establish a class-wide theory for proving their Colorado Consumer Protection Act claims in order to satisfy C.R.C.P 23's predominance requirement. Based on the plaintiffs' allegations that they were not relying on individual sales interactions, and without holding an evidentiary hearing, the trial court certified two classes. In October 2001, Reyher was injured in an automobile accident and received medical treatment from Dr. Brucker at the Arkansas Valley Regional Medical Center.

Dr. Brucker then submitted bills for the treatment to State Farm for reimbursement. At the time, State Farm contracted with Sloans Lake Managed Care to review and handle claims through its Auto Injury Management ("AIM") program. To determine the "reasonable and necessary" price for a patient's treatment, Sloans Lake's AIM program relied on a Medicode database (the "database") to compare the price of the treatment with charges for like services in the same geographical area. Based on recommendations generated by the database, Sloans Lake suggested repricing eight of Dr. Brucker's bills.

State Farm repriced those bills, compensating Dr. Brucker only for the amount it deemed reasonable. If you are seriously injured in a car accident, you will have to deal with your own insurance as well as the other driver's insurance. Surprisingly, State Farm had a more difficult time in the years of the immediate postwar era, due to increased driving and higher claims.

But with reorganization and changes of some methods, the company began to prosper again. In 1965 it entered the health insurance business, having already begun life and home insurance subsidiaries decades before. During the 1970s and 1980s, State Farm faced a variety of legal issues, some of which were industry-wide.

In the late 1980s and 1990s, it encountered new insurance challenges including increasingly severe natural disasters and the spread of AIDS. The trial court assumed that Plaintiffs' interpretation of the No–Fault Act was correct and recognized that these two questions could be common to the class. However, after rigorously analyzing Plaintiffs' class-wide proof, namely the nature of State Farm's claim review process, the trial court was satisfied that State Farm did not have a class-wide practice of relying solely on the database.

The trial court then determined that proof at trial would be predominantly individual—a determination within the trial court's discretion. We defer to this case management decision and recognize that Plaintiffs' interpretation of the No–Fault Act and theories of proving liability can be tested in individual trials on the merits. Ultimately, the trial court concluded that individual issues predominated over common issues because Plaintiffs lacked a class-wide theory of proving liability. Accordingly, we defer to the trial court's analysis of the evidence regarding Plaintiffs' class-wide theories of proof and resultant determination that individual issues predominate over common issues.

Plaintiffs could, for example, prove that State Farm had a company-wide practice of unlawfully relying solely on the database without investigation to reprice the class members' bills. State Farm considered the "True Stories" campaign a success and continued to air the television spots, along with new executions, into 2006. One of the new spots made its debut during the pregame ceremony of the 2006 Super Bowl. In 2004 State Farm's market share fell further, to 18.2 percent. The company set a goal of 400,000 new policies and exceeded that number by 225,000. Consumers surveys conducted after the start of the campaign also revealed significant improvement concerning positive brand image and likelihood for a non-State Farm customer to consider State Farm as an insurer.

The postwar years were chaotic and fraught with serious problems for the auto insurance industry. There was a shortage of dependable, well-educated personnel, as well as a severe lack of sufficient office equipment and office space. This was at a time when Americans were rediscovering their automobiles, driving them farther, and driving them faster.

State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Company Headquarters Phone Number Claims were flooding into insurance companies, their numbers rising 41% in 1945, and 57% in 1946. The total underwriting loss for the industry during 1945 and 1946 was estimated at $300 million, and for a few months in 1946, State Farm was losing money at a rate of $1 million a month. Claims were flooding into insurance companies, their numbers rising 41 percent in 1945, and 57 percent in 1946.

The total underwriting loss for the industry during 1945 and 1946 was estimated at $300 million, and for a few months in 1946 State Farm was losing money at a rate of $1 million a month. In the 1950s, State Farm held a contest among the agents, to come up with ideas to expand the State Farm business. Robert H. Kent, a State Farm agent in Chicago, came up with the idea of providing auto loans to existing policyholders.